Article Library

What is dyslexia and what can be done to help?

by David Morgan | 2 April 2019

Dyslexia can make learning to read a real challenge, but dyslexics are often exceptionally bright children, with incredible potential. We find that – with the right targeted support – every dyslexic can crack the code and start reading and writing well.

If your child is struggling with dyslexia, he or she isn’t alone. According to Chris Horn of the University of South Carolina, an estimated 6 to 10 percent of today’s students face this learning challenge. Some say that the percentage could be even closer to 20, since many people struggle with their reading and exhibit dyslexic patterns, but do not fit exact testing criteria.

20% is roughly the number of adults who have passed through the school system and not learned to read in the USA, according to the National Center for Education Statistics. Such statistics shed light on just how widespread reading difficulties are. However, this doesn’t change the fact that it can feel scary and overwhelming— especially when you’ve just received a diagnosis of dyslexia for yourself or your child.

But what does a diagnosis of dyslexia mean? Does it mean that learning to read is impossible? Is dyslexia a lifetime disability?

At Helping Children to Read, our answer is a resounding “no!”

Instead, our research has shown that almost all dyslexics can learn to read and spell. In fact, we have not had a single dyslexic not learn to read well on completion of our home support process in recent years. Most can reach the middle or top of their class. It is our experience that with the right tools, every child can gain the skills they need to read fluently and well. It is our mission to get those tools into the hands of every child.

Rethinking dyslexia: a label, not a diagnosis

When someone is given a dyslexia diagnosis, our greatest worry is that they take it as a label of disability, with a sentence of lifetime reading struggles. Some specialists will suggest this is the case, and say that a dyslexic child should accept the situation and switch to using “practical” tools like read-to-me software as a workaround.

We understand that if you have not seen dyslexics learn to read, then that would seem like good advice. But we could not disagree more with that view!

Learning with conventional phonics is often hard for dyslexics, but there are new and different strategies. If you support the decoding of words in the right way, children with dyslexia can still become proficient at it quite quickly, with good comprehension. By using trainertext visual phonics to help with the decoding and by addressing other causes of difficulty, we fundamentally change the way that dyslexics approach the written word. Once that switch of strategy has occurred, their reading can start to fly.

What is dyslexia? Really

Before we tell you how we view it, here is a quick look at some of the opinions you will find presented by other experts on dyslexia. As you start to read into dyslexia, it is quickly obvious that there is some variation in how people think about the term!

Below, we discuss some areas of contention among today’s different dyslexia groups.

Is dyslexia a genetic condition?

Some dyslexia organizations take the stance that dyslexia is a genetic condition. On their homepage, the American Dyslexia Association suggests that in dyslexia, “sensory perceptions are affected by genetic processes of development in the brain.” Additionally, these genetic processes are thought to be “transmitted by inheritance.”

Does dyslexia start in the brain?

Modern neuroscience has shed light on how the dyslexic brain underlie most reading struggles. Maryanne Wolf, who is a Tufts professor and the director at the Center for Reading and Language, explains that our brains are not “pre-programmed” with the proper circuitry for reading and dyslexics find it harder to develop the connections needed.

This view is echoed by neuroscientist Guinevere Eden, who directs the Center for the Study of Learning at Georgetown University Medical Center. Our brain must create “new circuits based on new connections,” using the systems in the brain that are already there.

Our focus is always on how to help a dyslexic develop that wiring in the easiest and quickest way.

Developing phonemic awareness (awareness of the individual sounds in each word) can be challenging, particularly for dyslexics. Dyslexia Training Institute co-founder Kelli Sandman-Hurley argues that brains of some people with dyslexia function and adapt differently from those without dyslexia. Dyslexia advocate, Emerson Dickman, agrees.

Is dyslexia a sign of poor phonological awareness and decoding skills?

Co-founder and co-director of the Yale Center for Dyslexia & Creativity, Sally Shaywitz, M.D., explains that dyslexics “have trouble matching the letters they see on the page with the sounds those letters and combinations of letters make.”

On its website, the Yale Center for Dyslexia & Creativity notes that dyslexia is a problem that happens when a learner experiences difficulty recognizing and processing “the individual sounds of spoken language.” Many of these modern dyslexia experts now believe that phonemic awareness and decoding weaknesses are at the core of most dyslexia.

Are dyslexics intelligent?

One area that is not in contention is whether dyslexia is a sign of poor intelligence – all of the experts agree that it’s not. As dyslexia advocate, Emerson Dickman, notes, dyslexia has no relation to a person’s intelligence or IQ. Sally Shaywitz, M.D. likewise explains that in dyslexia, the reading difficulties are often “unexpected” because they occur in “learners of average and above-average intelligence.”

Our view of dyslexia

Reading is a complex process. That means that there are many different ways it can go wrong, and there is no single cause for all reading difficulties. That’s why, at Helping Children to Read, we believe it is essential to understand that not all dyslexics are struggling with the same issues.

We track nine different causes of reading difficulty and several of them have strong correlations with the patterns often seen in dyslexics. Dyslexia is often referred to as a single phenomenon, but we believe that is not right.

Instead, you must look at each learner as an individual and address their unique problems in order to find a solution that works best for them.

Among the different groups of struggling readers, one group is particularly prevalent: children who struggle to decode words. According to literacy expert Tim Shanahan, 86% of children with reading difficulties have “problems with phonological awareness and decoding.”

These learners find it hard to work out the sounds and then blend them, and instead many will resort to guessing short words. Often, when children struggle with decoding, they will instead try to sight read words as whole objects, because it seems easier.

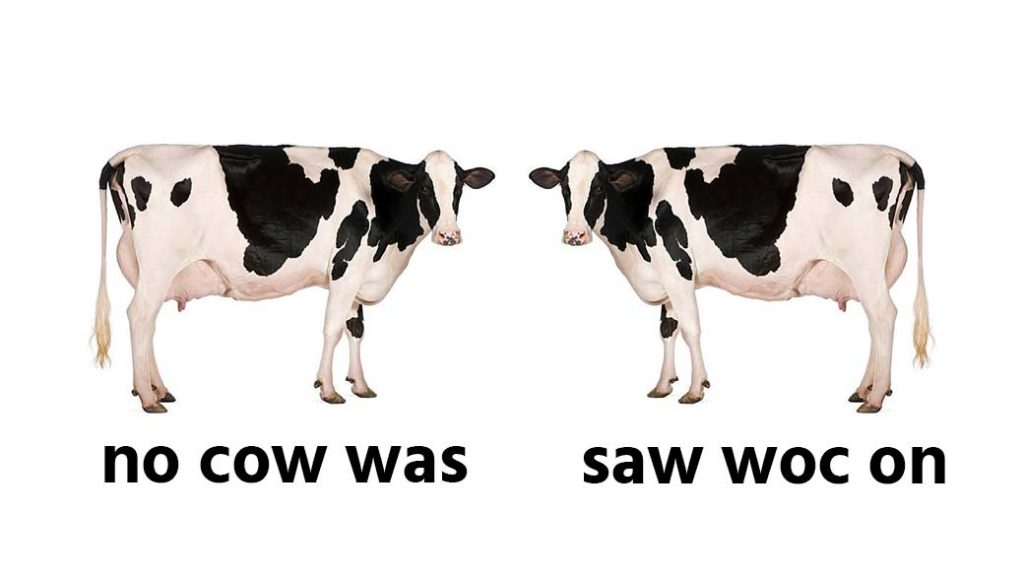

These learners try to memorize each word as an individual shape, just as they might recognize a cow or a zebra. A dyslexic with a particularly good visual memory can memorize hundreds of words this way, rather than decoding letter patterns into sounds.

This whole-word memorization leads to the confusion of small words, like this/that, from/for, them/there, and also to the flipping of b/d, on/no, of/for, was/saw, which are patterns you see with some dyslexics.

The image of a cow is still a cow when you flip it over. If you treat a word like an image in the same way, the word can easily become flipped in your mind, leading to confusion and mistakes. The famous dyslexic Leonardo da Vinci, for example, routinely wrote back to front as if in a mirror (although with very poor spelling!).

For very visual children, this small change in how they perceive words can lead to a lifetime of difficulty in reading. Children with particularly strong visual memories can often hide their troubles in the early years, because they are progressing.

As the International Dyslexia Association notes, these learners “manage to learn early reading and spelling tasks,” but begin to experience significant struggles when “more complex language skills are required, such as grammar, understanding textbook material, and writing essays.”

By the time the problem is recognized, the child has often experienced years of frustration.

Spelling frustration

Dyslexia is often associated with spelling difficulties too. Many dyslexics do quite well on weekly spelling lists because they memorize the words the night before. But two weeks later, those same words will have gone again.

The weekly memorization process is often a waste of time for them and encourages whole-word reading strategies. In our experience, when a dyslexic learns to read the right way, by subconsciously linking letter patterns to sounds, their spelling then begins to drop into place naturally, without spelling lists to learn.

When learning about how dyslexia affects spelling, it’s important to note that dyslexia shares some symptoms with another learning issue called dysgraphia. Dysgraphia involves a specific difficulty with the act of writing, Kate Kelly at online resource Understood explains. Dysgraphia and dyslexia often occur together, but dysgraphia has a few symptoms that are separate from dyslexia.

Learners with attention deficits, weak working memories, and slow word recall can find the process of learning to read extra challenging too. But, just like dyslexics, if you give them the right tools and support, we find they get good progress.

ADHD or just a reading struggle?

Specialist dyslexia tutor Debbie Abraham explains that dyslexia can be associated with apparently reduced concentration. This can be true, and attention deficit can sometimes be a cause of slower reading development. But in our experience, more often dyslexic children are struggling to focus because they find reading and writing hard. They usually take much longer to complete a writing or reading task compared to their peers. In turn, this can make students get bored with their reading and writing tasks and they appear to have low concentration.

When we work with these children, we find that they are usually capable of concentrating on other tasks without a problem. Their lack of concentration with reading and writing is caused by their difficulty with the task, rather than the other way around. In such cases, it is not attention deficit that needs to be addressed, but the root causes of the reading difficulty.

Emotional aspects of dyslexia

Some dyslexic individuals might also develop a general anxiety or fear about reading and even all of school. Once students notice that they are underperforming compared to peers, they might feel embarrassed and lack confidence, Abraham adds.

Similarly, homeschooled children might compare themselves to siblings, or feel general anxiety about how difficult it is for them to read and write. Children are often very aware of their reading ability relative to their peers, and it is natural for their self image to be impacted by an apparent deficit.

In extreme cases, we find that rising stress can impact the reading ability directly, because the stress response systems tend to shut down higher brain function as the body moves toward fight-or-flight response mechanisms. Well-intentioned support can accelerate this spiral into a crisis. If you have often seen a major tantrum during reading practice, you will be familiar with this pattern.

We do a lot of coaching of parents on how to support a child through their reading practice without triggering this stress response.

Functional vision issues

If you’ve ever had to reach for a pair of reading glasses, then you know how important being able to see well is to the reading process. But just being able to focus each eye on the words isn’t enough. In order to read the lines on a text, a learner needs to be able converge both eyes on the same spot and to track along the lines of text in front of them in little jumps.

In our experience, around 30% of dyslexics have some weakness in this convergence and tracking that has not been picked up by a standard eye test. The University of Waterloo confirmed this in a recent study.

The exercise routine for convergence and eye tracking that we describe on our website can usually fix this in a week or two. In most cases, the root cause seems to be cerebellar weakness, which is usually comorbid with some coordination weaknesses, and has been explored by Angela Fawcett and others. In other cases, it might be due to a magnocellular pathway weakness, as described by John Stein, which can also cause some auditory processing weakness.

An issue that is massively overdiagnosed is a difficulty with the black-on-white contrast of normal print on white paper. We find that only around 5 percent of struggling readers have this difficulty. You will come across tinted overlays being used a lot with dyslexics, as a result of the research by Helen Irlen.

They may not be a significant help for many dyslexics, but for some a tinted overlay can be a life-changer.

Auditory processing developmental delays

Long before a baby sees their first alphabet book, the ground is being laid for language development in their auditory cortex. Every word they hear from their parents helps build up those key connection – that’s why baby talk really is important!

When children have undiagnosed hearing problems early on, perhaps just because of a bit of glue ear, they can develop weaknesses in their auditory processing system that lead to confusion when they learn to read. Julia Carroll and others have explored how dyslexia can sometimes be related to problems with speaking too, which can be another symptom of this weak development of the auditory processing.

Auditory processing weakness is therefore often a developmental issue rather than a genetic one. With the right help, you can then see big improvements. We find that trainertext helps with the reading and also helps improve speech by clarifying what the sounds are in different words.

If there is a family history of auditory processing weaknesses or weak short-term memory processes, then reading progress can be slower and more difficult. But Stuart Rosen correctly points out that this is only relevant for a subset of the dyslexic group.

Many dyslexics are very eloquent and have a big vocabulary, but if there is any auditory processing difficulty it will make it more challenging for that child to rhyme, pronounce phrases correctly and sound out unfamiliar words. We find it can take them 12 months or more to overcome this, even with the help of trainertext.

The cause of confusing research findings

This heterogeneous view of dyslexia is the key, in our view, not only to delivering the right help, but also reaching relevant research findings.

If you run tests on a very mixed group, the results you get will show weak correlations and the conclusions you draw may be wrong. This is why there is so much confusion surrounding dyslexia, making it hard for parents, teachers and governments to deliver solutions for children.

Effectively it is like testing everyone with a cough to understand what causes coughs. The results you get will be very confusing, because there are lots of very different reasons for having a cough.

Does that mean dyslexia does not exist?

When we explain dyslexia in this way, people often ask if we think dyslexia does not exist. The answer to that question for me is “No, I do think dyslexia exists and I am probably a dyslexic!”

The term dyslexia was coined to describe the phenomenon of bright children who struggle to read for no known cause. Over time we have made progress understanding the different possible causes of their difficulty with reading, but dyslexics who learn to read are still in the group of children who struggled to read.

And that is useful because it will still be affecting them to some degree.

It is also useful because these people have shared experiences, shared challenges and many shared strengths.

It is those strengths that I like to focus on. As a group, dyslexics tend to do exceptionally well when you consider they have struggled with the most fundamental element of our education system.

Conclusions

When you understand the unique underlying reasons why an individual child is struggling to read, it is instantly easier to give them the right help.

The help needed varies from one dyslexic to the next. You can check the main symptoms of each of the main causes of reading difficulty that we describe here to see whether any of them are familiar. The one we see most often is a lot of guessing with short, common words.

Once you pinpoint the cause of reading difficulty for an individual dyslexic, it can normally be largely fixed in 60-90 short sessions with trainertext visual phonics.

David Morgan has an honours degree in mechanical engineering and a masters degree in education. David was a founding trustee of The Shannon Trust, started David Morgan Education, launched Helping Children to Read and invented pictophonics. In his spare time he likes to ski, sail and walk the hills.

David Morgan has an honours degree in mechanical engineering and a masters degree in education. David was a founding trustee of The Shannon Trust, started David Morgan Education, launched Helping Children to Read and invented pictophonics. In his spare time he likes to ski, sail and walk the hills.